When I entered the coffee world—and I wouldn't say the specialty coffee world, because it was, as I see it now, low-quality coffee—when I entered, I knew nothing about varieties, origins, and processing.

And I was exploring. So I could easily try Sumatran coffee, or Indian Monsoon Malabar, or Jamaican Blue Mountain, or pay crazy money for the expensive geisha cafe, which didn't have any roasting dates. And a classic: going to Starbucks to check out their single origins.

And there was always a conflict. Because I couldn't taste the flavors written there in the tasting notes on the coffee bags.

But until recently, I pretended I could. (And I'm far from the only one who did!)

I now know that, as it was a low-quality coffee, and the roast was quite dark, it would not have been possible to taste the jasmine flowers in that old, rickety Geisha, nor the strawberries in the Monsoon Malabar.

But the labels said so. And I was insisting that I felt it. Probably, if I were more confident and honest with myself, I would have used the words "stale," "old," "paper." But no. I didn't have enough vocabulary, and I hadn't learned at that point to trust my receptors.

Only after a while did I get into the routine of tasting, begin to eat more consciously, expand my palate, and, over time, be able to taste more and more things. But it's a training process. And I'm not a "supertaster" of any kind. It's just a training process of learning how to put what you're feeling into words, and do it quickly and accurately.

And when I started getting into that tasting routine, it really made me realize how lazy my brain was. Every tasting became a battle against my brain's tremendous laziness, and it continues to be so to this day. Every time.

I realized that if I knew the roaster, or the origin, and I liked the previous experience, I tended to give higher scores. So I discovered almost immediately that it's mandatory to taste blind if you don't want your expectations to interfere.

I realized that if I like the flavor of coffee, I tend to also evaluate acidity and body more highly, and not analyze them carefully. I started to focus more on each parameter.

I realized that the packaging, the brand image, how expensive it is, my first impression of how much the company invested, will automatically make me rate the coffee higher. It will distract me from the flavor itself, because I'll make a connection between the packaging and quality. It also works the other way around: if I'm not impressed with the brand and the packaging, I may reduce the points when I'm tasting it. My brain is creating a connection that doesn't exist in reality.

And the list goes on and on; I'll write later about the tasting itself, which can be useful, as well as useless, if that topic interests you.

Right now, my questions are about something else.

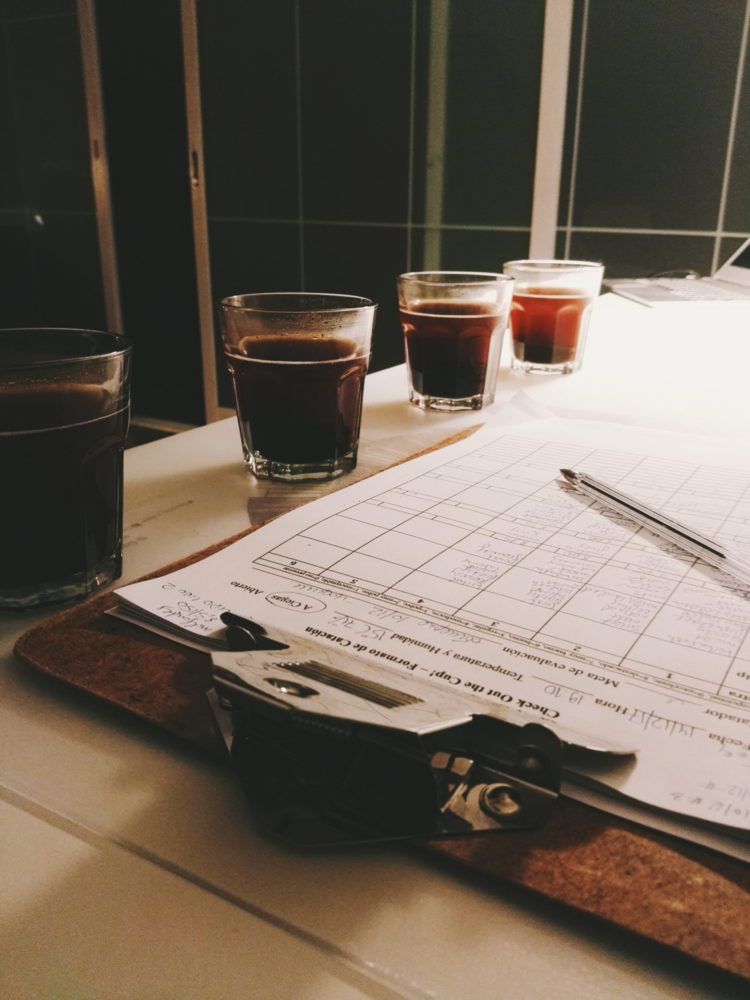

I recently tasted a coffee, "X." In two different locations, the same coffee, within a one-month period. The tasting notes on the label say, let's say, "mango." But if you cup it, blind, you'll simply feel the roast. Burnt, toasty, charred, smoky—that's what I wrote on my cupping form while I was blind-tasting it. Twice.

So I'm not even saying it doesn't taste like mango, but it does taste like pineapple or hazelnut, and the tasting notes are inexact, but more or less close.

I'm saying there's no trace of specialty coffee quality in the coffee's flavor, and the only thing you can find is the flavor of the roast itself. There's not even the possibility of adding "nut" to it, because there are no nuts.

But then I saw several people writing about that particular coffee and repeating the “mango” story.

And I repeat, there is no doubt that this coffee has notes of "mango," because there is none.

So the reality is, once again, revealing. It means that many people who write about coffee, who write about food, don't take the time to taste. They're writing about flavors, but they don't trust their own sensations; they rely on someone else's misleading descriptions.

You don't have to be a real professional in sensory evaluation.

All of us, when we start tasting, start with very poor vocabulary and end up using only 6-10 descriptors.

We can't taste the "handle" yet, but we use the words "roasted," "smoky," "chocolatey," "fruity," "almondy," "citrusy," "floral": those general descriptions are enough—yes, they are ENOUGH—to make an honest assessment, in this case, of the coffee you're drinking. Yes, you won't look as smart as if you were writing "This coffee tastes of rose petals and amaretto liqueur, with some delicate notes of clementine peel"—you won't look as good, no.

But on the other hand, it's better to keep trying and give an honest description of the coffee you're drinking. Yes, it will be short, like "chocolate," "full-bodied," "balanced," but you won't put yourself in the foolish position of writing that it tastes like mango when the coffee is totally burnt.

And the descriptors will come with time. When you learn to connect what you feel with words. It will come. It always comes. You don't need any special talent for that. All you need is to keep practicing, stay connected to your sensations, and be impartial. It takes time, but it always comes.

That's all for now.

As always, I'm just trying to say that the time invested in mastering a skill is always worth it. And tasting is an essential skill in the food industry and, therefore, in specialty coffee.

In other words, don't be afraid to say, "You know, dude, I can't feel the handle."

Because chances are you're right.