Jean Zuluaga Interview with the coffee exporter

"What's up, why spend fifteen thousand euros on a toaster?" "Are you already a specialty micro-roaster? I don't think so."

Jean reviews his career in the coffee world in a critical yet profound way. "My earliest memories of coffee are with my brother during the harvest, swimming among mountains of parchment coffee," he says.

To start, tell us where you're from.

I consider myself a citizen of the world. My parents are Colombian, but I was born and lived in the United States until I was eleven. Then I moved with my mother to Spain, where I spent my teenage years and truly have my own life. It's true that I alternate that American foundation with the European culture I've acquired over the years, but without abandoning my Colombian roots, as I travel every five or six months to stay connected. This has allowed me to open my mind a little and see that each culture has its own characteristics.

Where do you work and what is your role?

I'm in a family business: OPCE (Specialty Coffee Producers Organization SL).I have entered the business and am now in charge of imports and quality control in Spain and the rest of Europe.

When did you first get in touch with the world of coffee?

I was born into the coffee industry. My father's family is from Manizales de Caldas (we're talking about the heart of the coffee-growing region). He's been in the coffee industry since he was fourteen. My first memories of coffee are with my brother during the harvest, swimming among mountains of parchment coffee. Those are my first memories. At that time, my father had a coffee farm in Chinchiná.

-What is a coffee purchase?

They are the intermediaries between producers and the industry, which are the coffee mills. They collect coffee, usually finish drying it in silos, and then resell it to the mills. In the 1990s, there were several different players: producers, coffee buyers, mills, exporters, and then the coffee left the country.

The process has become much more complex today. Today, we are buyers, millers, and exporters. We're even roasters for local products. We've been growing and adding parts of that production process to the family process. It's in my blood; it's something my brother and I share, and we're trying to take it to the next level.

How is specialty coffee evolving in Colombia?

There, due to our geographical location and abundant water resources, we specialize in washed coffees. Now, what's happening? One of the biggest dilemmas that has existed in Colombia over the last forty years is the market-determined price. Market value plus a differential based on minor quality characteristics, but that's the basis for everything.

What happened? About five years ago, a transition began. They saw that Central American countries were developing other types of processes, and there was starting to be a demand for specialty coffees. This means you can play with the price; you're out of the market. The regulations for exporting coffee in Colombia are changing. They liberalized the market so you can export coffees that don't meet the excelso regulations, which are coffees that are labeled "product of Colombia" and not "coffee from Colombia." That was the window people found to innovate with different processes, break out of the market, and also improve their income.

But we're still in the early stages in that regard, and the first to do so are farms with the financial resources to invest and develop these types of processes, risking their harvests.

We, as exporters and as part of the learning process, We worked with a pilot farm that was one of the first to introduce natural varieties. Their first harvests went to shit, everything fermented.That stabilization process, the evolution of the microorganisms, the temperatures used to stabilize, all of this was completely new to us. Since then, we've been learning from this farm and seeing what the market offers and the price differentials.

Obviously, these types of processes make the product more expensive because everything has to be done more slowly, and the cup profile improves. Now we're playing with tasting points, a process, a story behind it, traceability... My brother is the one who's at the origin; he's in contact with the farms. He now has about five farms and is expanding. He's implementing a protocol for different processes, and we're learning little by little.

What impact has the FARC's laying down of weapons had on the sector?

The Colombian countryside is extremely dangerous. Consumer countries are unaware of this. The FARC controlled much of the jungle in the south of the country, Cauca, Nariño and southern Huila. Many areas were abandoned because of this cause.These are unexploited areas, but with tremendous production and quality.There are people who are starting to go to those areas to buy, but the guerrilla is not over yet and they are taking many risks trying to get coffee out of there.

It is not so easy to grow and extract coffee in Colombia, and that in turn makes it wonderful because it makes it a complete adventure.Many risks are taken.

Let's change the subject. I want to ask you about DISPAR. That's where I met you, and I'd like you to tell our readers about the space you created in La Coruña.

It was an idea I had in my head and had to execute sooner or later. The opportunity arose when I ended up in Coruña, and I said, now is the time to introduce a new idea into my life.

The idea was so clear in my head that I told myself: the day I open my business, I'll have the equipment I want, without worrying about whether this or that is expensive or cheap. I was clear about which coffee maker I wanted for this project. The Marzocco Strada was a turning point in espresso machines, especially for my generation. I knew it was the only machine I would accept for the concept I wanted to introduce. Taking everything to the extreme.

DISPAR by definition means going against the current, and that was part of what I wanted to conveyI wanted to demonstrate that there was another level within specialty coffee shops, and that was by giving absolute importance to the product. I didn't want a coffee shop; I wanted a space where coffee could be consumed.

Risking everything for a very clear and precise idea: to specialize in espresso, a single origin (Colombia), and without any other accompanying products. Let the coffee speak for itself.

Taking it to the absolute extreme, there is nothing like it in Spain or Europe, as far as I know.

Showing people that there could be a completely different concept when it comes to drinking coffee. Spain remains a country where the hospitality industry and coffee culture are deeply rooted. In order to introduce a completely new concept, I had to go to the extreme, which was a small establishment specializing in takeaway, but without abandoning the concept of having a cup of coffee on-site.

– How was it accepted?

The beginning was very difficult; people couldn't understand so much extreme. I'm always a black and white person; I don't like shades of gray, and that was something I had to represent there. The first six months were truly chaotic. I didn't want to advertise; I wanted people who walked through the doors to be curious, and I wanted to satisfy that curiosity. That was the real goal, and I knew it would take time and patience for them to believe in it.

-Were the customers showing interest?

Yes, you have to generate that curiosity in the customer. It was part of my responsibility at that location to generate interest. Over time, many people became curious. You can't expect someone who's used to drinking a coffee with lots of milk to drink a double espresso. But I could guide them through the process of bringing them to the quintessential espresso. How do we do it? We start with a coffee with milk and lots of sugar. By choosing the right ingredients and working the milk well, we can extract a lot of sweetness. From there, we begin to introduce drinks with less milk to adapt the palate to more intense flavors. The next step? Let's eliminate the milk. We replace the milk with water to create a diluted drink with coffee as the sole protagonist. And now we can start playing with espressos.

I did this learning process with many people, and it really worked. They were able to adapt their palates little by little. We can't be so tyrannical as to try to change our consumption habits overnight.

The typical case of "no, there's no sugar, why isn't there sugar?" At first, not even God paid any attention to me. They thought I was crazy. After the first six months, people saw I was serious. Time is crucial in small towns; it ultimately sets the tone for whether people believe in you.

What negative things did you find out?

There are some things I can't fight. Someone I'm trying to sell a different concept to can't judge me solely on the economic factor. You can't tell me my coffee is bad because it's too expensive. I couldn't tolerate this, and it caused me tremendous frustration.

Another mistake was the size of the space. People weren't prepared for something like this. There's a culture of sitting down and having a drink, whatever it is.

It was also a challenge selling coffees with a pronounced acidity. I had to introduce much simpler coffees. The base was balanced coffees, very sweet and with a mild acidity to make them easier for people to introduce. This left me with little flexibility when choosing raw materials. This always frustrated me, because those of us in this business like to experiment.

How do you see specialty micro-roasters in Spain?

I see them very badly. How many of these micro-roasters have the experience to offer this product to market with such differentiated values and a very different price from the established one?

It happens like with many baristas who are starting out. Is an eight-hour course enough to start a business? I don't think so. Why? Because it discredits the experience of the people who are actually behind it, with a foundation, a rationale for selling the products at the right prices.

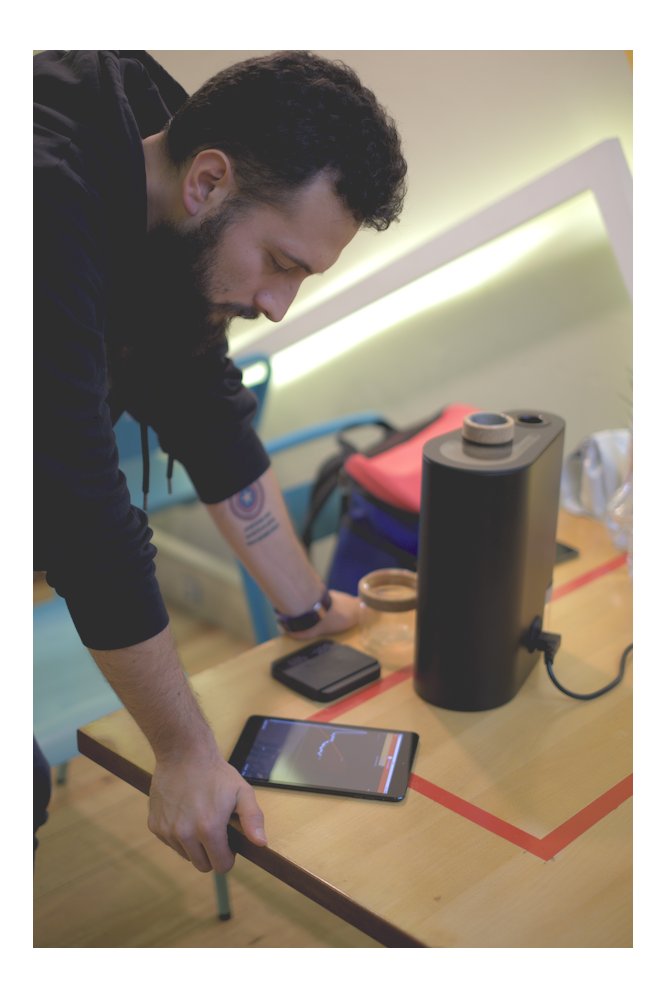

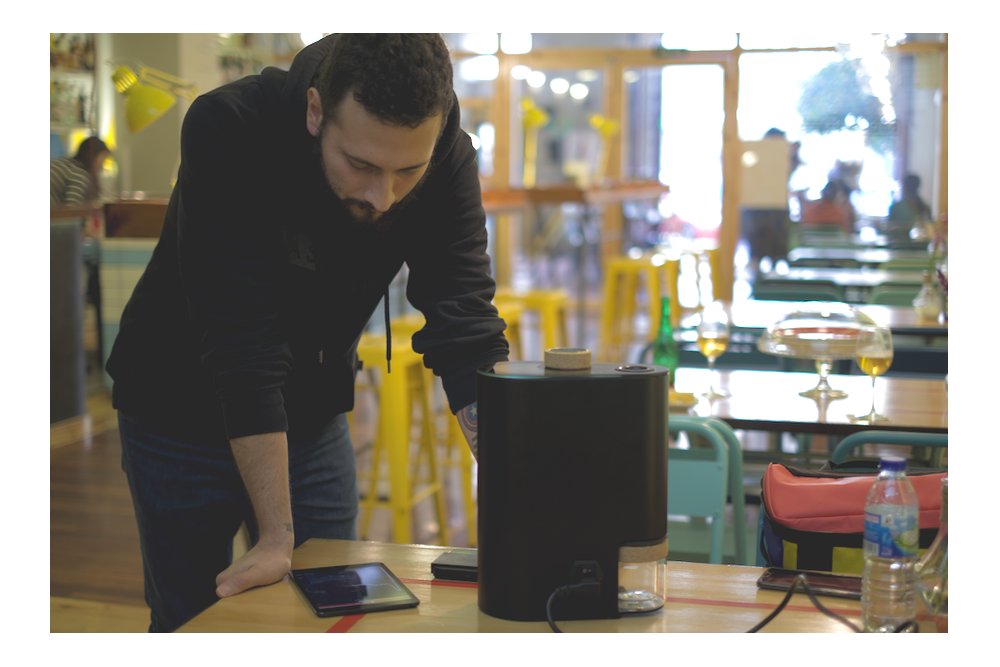

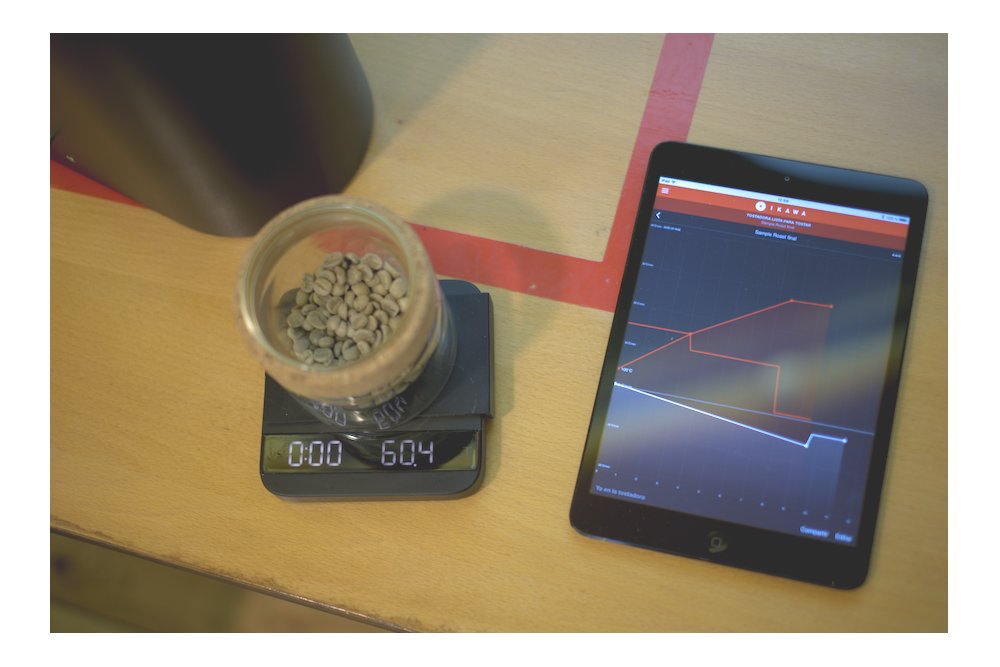

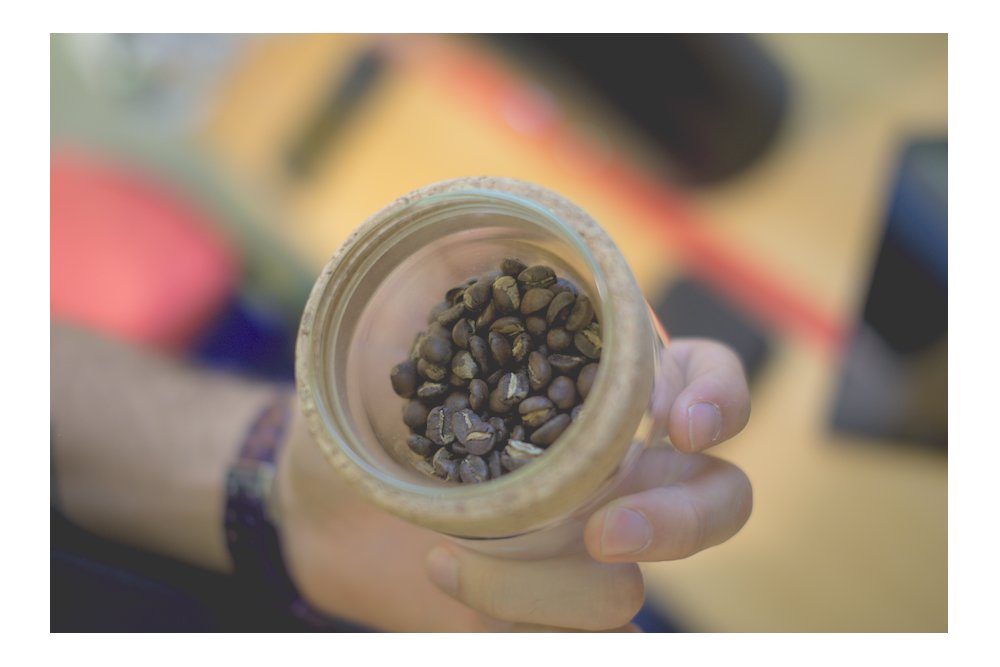

It's not about having good raw materials, roasting them and selling them, no. So what? It happens with understanding that raw material, with understanding the composition of that product, con the selection process or quality control? What's up, why spend fifteen thousand euros on a toaster? Are you already a specialty micro-roaster? I don't think so.

Is investing in creating a specialty coffee micro-roastery in Spain a risky business today?

Yes, it seems like suicide to me. Aside from my background in this industry, I'm a financier by training, and I'm fully aware of the numbers behind this type of business. When I see a new business like this, I wonder: Do they really understand the five-year viability? If you do a market study, the numbers aren't going to work for you.

Tell me about a coffee you tried and will never forget.

I have one that left a mark on me very recently. St. Petersburg, January, very cold, a frozen city. My brother and I were walking down the street and a scent appeared and we said, wow, what is this? And there we came across a store. Double B. This is a Russian specialty coffee chain, with a strong presence in Moscow and St. Petersburg. I remember going in and up to the second floor, where we both ordered Kenyan coffee, espresso, and filter coffee. When I tried that filter coffee, I said, "Fuck, what is this?" It is the coffee that marked a before and after for me in the concept of specialty coffees.Because they created the perfect atmosphere for me. Due to the very cold, wintery circumstances, and in a completely unfamiliar place, I didn't expect to find a cafe like this.

How do you take your first coffee in the morning?

I'm currently using an Italian coffee maker. My partner and I are just starting to experiment with it.

Finally, what is your favorite origin?

Colombia. But not because of the connection I have, but because of the number of options and alternatives there are in that country.

How to contact Jean?:

Tel- 690 33 36 30

I want to thank Jean Zuluaga for his time, and Juan Zabal for allowing me to conduct this interview at his impressive "La Olímpica" location and showing me his roastery for his "Astro Café" brand. Their kindness and hospitality captivated me.

The Olympic

Alfredo Vicenti Street, 39, 1

5004 A Coruña

Tel- 881 08 01 06